What is Myopia?

Myopia, or nearsighted, is a condition where distant objects appear blurry, while close objects appear clear. The most common symptoms include children holding things close to their face, or squinting to see distant objects.

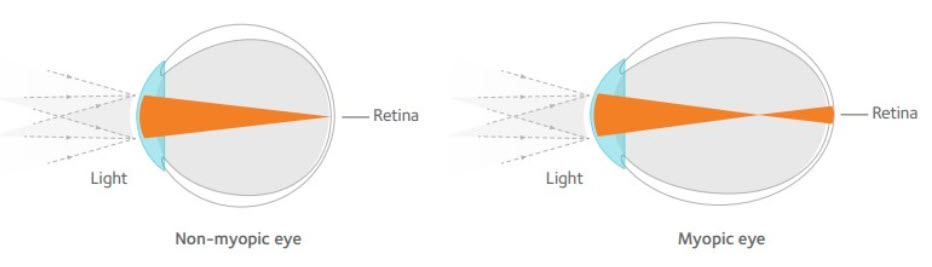

Myopia can occur in two ways:

- the optic system (cornea and crystalline lens) having increased focusing power

- elongated axial length (length of the eyeball) during normal development

As a result, there is a mismatch between the power of the optic system and axial length, which results in images focusing in front of the retina.

According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, myopia is the most common refractive error for those younger than 59 years old1

In 2010, 27% of the world’s population had myopia. That number is expected to rise to more than 50% by 20502

The World Health Organization (WHO) identified the increase in myopia as the number one health threat facing vision worldwide because of its statistical association with eye disease.

This includes retinal detachment, subretinal neovascularization, macular degeneration, cataracts, and glaucoma. Any level of myopia can be considered a risk factor for these diseases.

Nowadays we can do more than just prescribe a standard pair of glasses or contacts. We have the tools to delay myopic onset and reduce its rate of progression.

What can I do now?

- Get your eyes examined! Children as young as six years old with less than +0.75sph of hyperopia are at an increased risk of developing myopia3

- Take breaks when reading: a two minute break after every 30 minutes of near work

- Spend at least 90 minutes of outdoor time per day. A neurotransmitter called dopamine is stimulated by the sun. Animal models show that dopamine and vitamin D controls the elongation of eyes.

- Limit time on near work: children who spend more than 3 hours of reading a day had a higher risk of developing myopia4

- The WHO recommends no longer than 1 hour screen time per day for children aged 2-45

- Dr. Chow recommends no screen time for children less than 1 years old. For six years olds, no longer than 2 hours per day.

Will my child’s vision continue to get worse every year?

Once a child develops myopia, the average rate of progression is about 0.50 diopters (D) per year9

A diopter is the unit used to measure glasses and contact lens prescriptions. Based on expected progression rates, an average 8-year-old child who is -1.00 D, may be -6.00 D by the time he or she is 18 years of age. Myopia generally stops progressing in the late teens to nearly twenties.

What are the ocular disease complications associated with high myopia?6

- Myopic maculopathy

- The Blue Mountains Eye study looked into 3654 subjects for evidence of myopic maculopathy. Subjects with less than 5 diopters of myopia had a prevalence of 0.42% for maculopathy compared to 25.3% in eyes with more than 5 diopters of myopia. The prevalence was over 50% for eyes with greater than 9 diopters of myopia.

- Retinal detachment

- The Eye Disease Case-Control Study in the US compared 253 patients with idiopathic retinal detachment and 1138 controls. Patients who had between 1 to 3 diopters of myopia had an odds ratio of 4.4x compared to 9.9x in patients who had between 3 to 8 diopters of myopia.

- Glaucoma

- A meta-analysis looked into myopia as a risk factor for glaucoma with data from 11 different studies. It showed that patients with up to 3 diopters of myopia had an odds ratio of 1.65x compared to 2.46x in patients with more than 3 diopters of myopia.

- Cataract

- The Blue Mountain Eye study also looked into the association of myopia and posterior subcapsular cataract. The odds ratio were 2.1x, 3.1x, and 5.5x for low, moderate, and high myopia, respectively. The Salisbury Eye Evaluation project found similar associations with odds ratio of 1.59x for myopia between 0.50 and 2 diopters, 3.22x for myopia between 2 and 4 diopters, 5.36x for myopia between 4 diopters and 6 diopters, and 12.34x for myopia of at least 6 diopters.

Treatment options at Eyes4kids

- MiSight® 1 day contact lenses: The child wears contact lenses during the day and removes them at night. These lenses have an optic zone concentric ring design with alternating vision correction and treatment zones. It is the first and only soft contact lens FDA-approved to slow the progression of myopia in children, aged 8-12 at the initiation of treatment. There was a 59% reduction in refractive error compared to control, a 52% reduction in axial length compared to control. 42% of patients in this lens had -0.25sph or less of myopia progression8

These results were seen in children wearing these lenses for a minimum of 10 hours/day, 6 days/wee - Custom soft lenses for myopic patients with astigmatism. Similar design to above, but caters to patients with astigmatism, and/or myopia higher than -6.00sph. These are usually quarterly fit modalities (lenses are used for 3 months at a time, daily wear, not to be slept in)

- Atropine eye drops: this medication is used before bed each night. The side effects are pupil dilation and mild blur at near most noticeable during the first few weeks of using the drops. Because of this, progressive additional lenses (PALs) and transitions (photochromic) lenses are usually recommended. Atropine 0.01% has been shown to slow myopia progression by 50%7

Parent resources:

- https://www.aoa.org/documents/HPI/HPI%20Myopia%205_2019.pdf

- Mykidsvision.org

- Treehouseeyes.com

- myopiacontrol.org

Citations

- Gong, Qianwen, et al. “Efficacy and Adverse Effects of Atropine in Childhood Myopia: A Meta-Analysis.” JAMA Ophthalmology, American Medical Association, 1 June 2017, ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28494063.

- Holden, Brien A, et al. “Myopia: a Growing Global Problem with Sight-Threatening Complications.” Community Eye Health, International Centre for Eye Health, 2015, ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4675264/.

- Zadnik K;Sinnott LT;Cotter SA;Jones-Jordan LA;Kleinstein RN;Manny RE;Twelker JD;Mutti DO; ; “Prediction of Juvenile-Onset Myopia.” JAMA Ophthalmology, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25837970/.

- Guggenheim, Jeremy A, et al. “Time Outdoors and Physical Activity as Predictors of Incident Myopia in Childhood: a Prospective Cohort Study.” Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science, The Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology, 14 May 2012, ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3367471/.

- Stiglic, Neza, and Russell M Viner. “Effects of Screentime on the Health and Well-Being of Children and Adolescents: a Systematic Review of Reviews.” BMJ Open, British Medical Journal Publishing Group, 1 Jan. 2019, bmjopen.bmj.com/content/9/1/e023191.

- DI;, Flitcroft. “The Complex Interactions of Retinal, Optical and Environmental Factors in Myopia Aetiology.” Progress in Retinal and Eye Research, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22772022/.

- D;, Chia A;Lu QS;Tan. “Five-Year Clinical Trial on Atropine for the Treatment of Myopia 2: Myopia Control With Atropine 0.01% Eyedrops.” Ophthalmology, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26271839/.

- Chamberlain P;Peixoto-de-Matos SC;Logan NS;Ngo C;Jones D;Young G; “A 3-Year Randomized Clinical Trial of MiSight Lenses for Myopia Control.” Optometry and Vision Science : Official Publication of the American Academy of Optometry, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31343513/.

- Donovan, L., Sankaridurg, P., Ho, A., Martinez, A., Smith, E., & Holden, B. (2010, April 17). Rates of Myopia Progression in Children. Retrieved June 16, 2020, from https://iovs.arvojournals.org/article.aspx?articleid=2370367